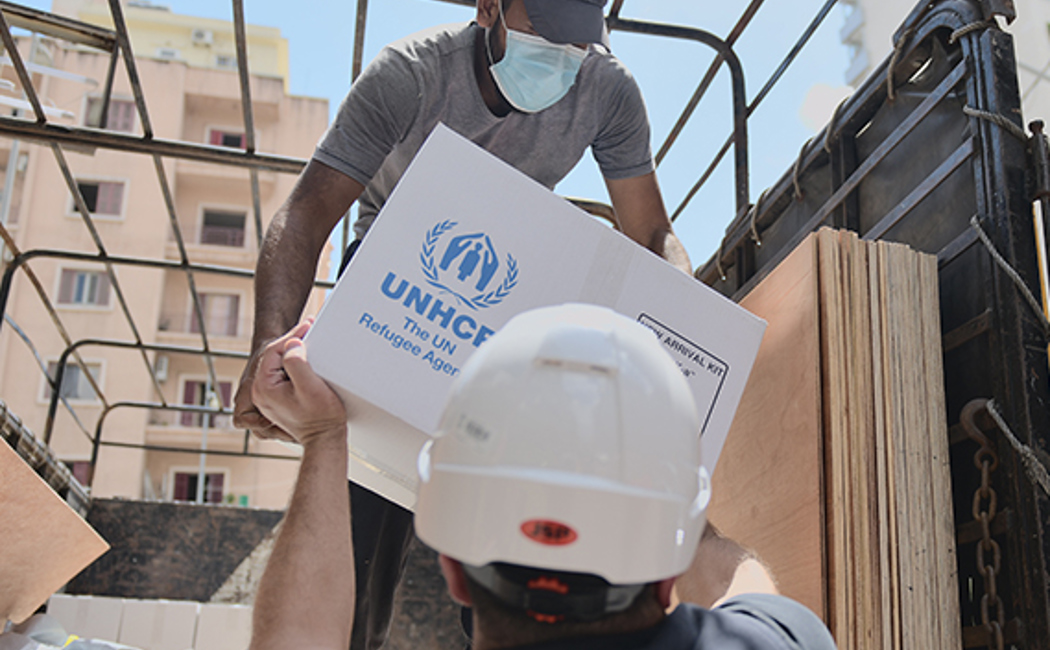

When violence erupts and disaster strikes, your support allows UNHCR to go straight into action. UNHCR is often first in and last out in a refugee crisis, and is able to have staff and supplies on the ground within 72 hours.

We bring you stories from refugees and displaced people fleeing conflict and disaster, as well as personal accounts from Australian donors, fundraisers and field workers.

Australia for UNHCR is the UN Refugee Agency’s national partner in Australia, raising funds and awareness to support displaced people across the globe. Nobody chooses to be a refugee, but we can all choose to stand with refugees in their time of need.

Each of us has the power to make a difference. You can support refugees by fundraising, giving a gift or attending our special events.

A donation to Australia for UNHCR will bring life-changing assistance to people fleeing conflict, disaster or persecution. Your regular and one-off gifts help displaced people on their journey to safety.

Lebanon

Lebanon